|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| |

Report

of the Long Island Botanical Society

Field Trip to the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland, Canada

|

|

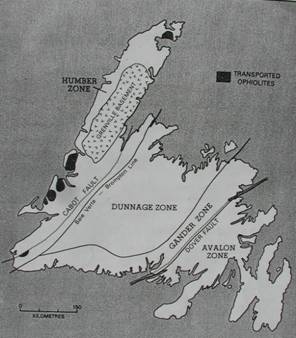

According to plate tectonic interpretation, the Great Northern Peninsula was the edge of the North American continent in Cambrian time 600 ma (million years ago), when a proto-Atlantic Ocean had opened up between North America and Europe/Africa (Figure 2 in Rogerson 1983). A carbonate bank, similar to the present-day Bahamas, formed offshore on the shallow continental shelf and fine-bedded shales seen at Broom Point and Green Point were laid down in deep water between the continental shelf and the deep ocean floor. [Those at Green Point mark a “type locality” for the boundary between the Cambrian and Ordovician periods.] Between 500 and 450 ma, in Ordovician time, the proto-Atlantic began to close as the continental plate, on which the great northern peninsula rode, began to be subducted eastward into a deep-sea trench; the resulting melting gave rise to a chain of offshore volcanic islands similar to Japan off the coast of China today. The lighter continental crust rebounded upward breaking off a part of the ocean crust and mantle which slid westward over the continental rocks to form Table Mountain;

|

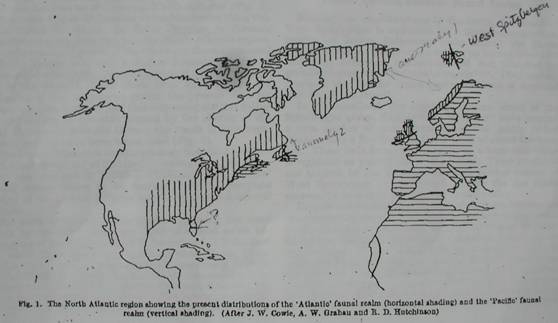

The opening and closing of a proto-Atlantic solves one major puzzle regarding the distribution of shallow-water marine fossil faunas of Cambrian-Ordovician age. The fossils of eastern Newfoundland (Avalon zone) match those of Morocco whereas fossils of western Newfoundland fossils (Humber zone) match those in adjacent Labrador. Likewise there are marine fossils in Great Britain and Scandinavia that match Greenland fossils rather than those in the rest of Europe. This can be explained if the fossils were laid down when the proto-Atlantic was open; when it closed and the current Atlantic Ocean re-opened along a slightly different line, it left mismatched fossil faunas adjacent to one another (Figure 1 in Wilson 1966).

|

Geology at the LIBS Stops by Ann F. Johnson

According to two geologic maps of the area (Newfoundland and Labrador: travellor’s guide to the geology and Geology, topography, and vegetation of Gros Morne National Park) the rocks underlying our various stops were as follows:

- 7/5/06:

rare orchid along a tributary of upper Humber River on way to Richard

Squires Provincial Park – Carboniferous shale (youngest bedrock

in

Newfoundland).

- 7/6/06: Lomond River hike – Ordovician

limestone;

head of trail to Green Gardens-Cambrian gabbro, pillow basalt and

shale; Table Mt - Cambrian ultramafic rock (peridotite).

- 7/7/06: Bakers Brook, Arches Provincial Park

– Ordovician mélange (broken sedimentary rocks);

Bellburns – Ordovician limestone and dolostone.

- 7/8/06: Philips

Garden and Point Riche – Ordovician limestone and dolostone.

- 7/9/06: Flowers Cove –

Cambrian limestone and dolostone; Cape Norman – Ordovician

limestone and dolostone.

- 7/10/06: Burnt Cape – Ordovician

limestone and dolostone.

- 7/11/06:

L’anse aux meadows – Precambrian/Cambrian

sandstone, shale and conglomerate, lava and ash deposited in deep ocean

basins.

- 7/12/06: Goose Cove – Cambrian/Ordovician

lava and

ash from deep sea floor; Great Behat - Precambrian/Cambrian sandstone,

shale and conglomerate, lava and ash deposited in deep ocean basins;

Nameless Cove (thrombolites) – Cambrian limestone and

dolostone.

- 7/13/06:

Broom Point (and Green Point): Cambrian/Ordovician limestone

conglomerate, thin-bedded limestone, chert, and shale.

- 7/13/06:

Berry Pond – Ordovician mélange (broken sedimentary rocks).

- 7/14/06: Lomond River – Ordovician limestone.

Island Vegetation

The island of Newfoundland lies at the eastern limits of the Boreal Forest Region. This assignment of biome is due to the dominance of such coniferous trees as Picea glauca, Picea mariana and Abies balsamea. Boreal evergreen coniferous forests are often referred to as “taiga,” a Russian word for “dark forest.” Deciduous trees, mainly birch and poplar, are generally confined to sheltered spots and interior valleys. “About half of Newfoundland is forested, but much of the higher land in the south and west consists of ‘moss barrens’ which are [devoid of timber].” Fraxinus and Ulmus trees are confined to the warmer climate of southwest valleys. Betula lutea and Pinus strobus are common in the center and west. Abies balsamea and Picea mariana are general everywhere in the lower lands except in the northeast, where [Populus tremuloides] and [Betula cordifolia] stand the cold climate better” (Belanger, 2006). Bogs and other wetlands are common features of the Boreal Forest zone. These are among the most productive and diverse habitats in that zone.

Vegetation of the Northern Peninsula

Damman (1983) recognizes the Northern

Peninsula as lying in the

Northern Boreal subdivision of the “[B]oreal

[Z]one” on Newfoundland. The Northern Peninsula

comprises three eco-regions: Northern Peninsula Forest, Long Range

Barrens and Strait of Belle Isle Barrens (Photography of Wildlife

& Natural Areas of Newfoundland, Eco-regions, undated).

Damman (1983) recognizes the Northern

Peninsula as lying in the

Northern Boreal subdivision of the “[B]oreal

[Z]one” on Newfoundland. The Northern Peninsula

comprises three eco-regions: Northern Peninsula Forest, Long Range

Barrens and Strait of Belle Isle Barrens (Photography of Wildlife

& Natural Areas of Newfoundland, Eco-regions, undated).

The Northern Peninsula Forest, divided east from west by the Long Range Mountains comprises flat lowlands to the west and foothills to the east. This regional type occupies the coolest climate on the island, has the lowest precipitation, and is said to have low evapo-transpiration. Abies balsamea (well drained sites) and Picea mariana (poorly drained sites) dominate the forests up to the higher elevations. The “zonal sites” are occupied by Abies balsamea/Dryopteris campylopteris/Hylocomium forest (Damman 1983). White birch and pine, red maple and trembling aspen are north of their northern limit in this region. “Ombrogenous peatlands cover extensive areas on flat trerrain. They are mainly treeless, low plateau bogs with a well-developed pattern of strings and pools. They occur even on gravels and sands in topographically well-drained positions and often form transitions to blanket bogs on gently sloping areas. On such deposits, a thin indurated [iron] or [iron-manganese] pan, placic horizon, occurs in mineral soil under these bogs” (Damman 1983).

Long Range Barrens occupy the highest elevations on the mountains, other highlands and plateaus. Climate consists of short cool summers and long cold winters, and features persistent snow cover. These are treeless areas with tuckamoor (also referred to as krummholz or dwarfed trees) of spruce (exposed) and balsam (in sheltered spots).

Strait of Belle Isle Barrens occur on flat and rocky areas along the western coast and on hills to the east. Here the summers are short and cool, the winters are long and cold with the lowest temperatures on the island. Pack ice is present until early summer. There is a potential for a freeze at any time of the year (no summer). Precipitation is low, fog is persistent. Vegetation consists of (1) treeless barrens (cushion plants and prostrate perennial herbs) on gravel-covered ground, (2) tuckamoor and (3) tundra (low vegetation of mixed dwarfed willow and birch shrubs, prostrate heath shrubs, graminoids, and some delicate herbs; with lichens and cushion plants dominating on the thinnest soils and rock outcrops) (Photography of Wildlife & Natural Areas of Newfoundland, Eco-regions, undated)

Origin of the Flora

“The flora of Newfoundland is particularly fascinating, not because of its richness but because of its paucity and the odd assemblage of plants. Newfoundland... gets the tail end of many different floras. Many plants reach the extreme of their range or ecological tolerance here. In addition, they do not fill the same ecological niche here that they do elsewhere. All of this leads to many delightful discoveries for anyone studying the flora”.

The flora is essentially that of the boreal forest with a number of “elements” added: (1) Arctic species at high elevations and coastal cliffs (Juncus triglumis, Saxifraga oppositifolia, S. aizoides, S. caespitosa, Salix vestita, Dryas intergrifolia and Lesquerella arctica (Fuller 1919); (2) coastal plains species found from New Jersey north extend to the island and often grow in close association with arctic species, (3) a number of Cordilleran species, which have their main distribution in western North America, are found on the mountains and unstable soils of western Newfoundland; (4) Amphi-Atlantic species that occur on both sides of the North Atlantic (e.g., Calluna vulgaris and Pedicularis sylvatica, Fuller 1919) and (5) many introductions which reflect the past and recent human history. Temperate-boreal species that are common further south, even on Cape Breton are absent here, e.g., eastern white cedar and its associates. According to Fuller (1919), the presence of high arctic species on Newfoundland’s west shore was said by Fernald to be due to the “calcareous” habitats that exclude temperate-boreal species [because of the limitation of nutrients that are readily available in “siliceous” (i.e., “malfic”) soils].

Newfoundland has a total of 1267 species of vascular plants. These comprise Fern Allies (23), Ferns (40), Conifers (10), Monocots (375) and Dicots (821). A number of families are “prominent”: Ericaceae (heath family), including Vaccinium vitis-idaea, Vaccinium angustifolia, Vaccinium uliginosum, Kalmia spp., and Ledum groenlandicum; Pinaceae (pine family), with 9 species that are often dominants in the landscape: white spruce (Picea glauca), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), and black spruce (Picea mariana); Cyperaceae (sedge family) has 139 species which are found mostly on peatlands and other wet habitats. They are especially prominent in streamside habitats, especially Carex (sedge) and Scirpus (bulrush) (Scott 2005

Plants Observed and Notes

Common plants of the Boreal Forest zone are ericaceous shrubs, willow, alder, Labrador tea, blueberry, bog rosemary, feathermoss, cottongrass, sedges, kalmia, heath, highbush cranberry, baneberry, wild sarsaparilla, bunchberry, shield fern, goldenrod, water lilies and cattails (Anonymous 2006).

Coastal maritime flora comprises spermatophytes, some pteridophytes, and many non-vascular plants (including mosses, algae and lichens) that live in or near the edge of the sea. Some algae and lichens live within reach of the wave spray. Marine algae live in the intertidal zone and withstand the constant pounding of the surf.

Bibliography

Anonymous. 2006. Boreal Shield [Ecozone], Canadian Biodiversity. http://www.canadianbiodiversity.mcgill.ca/english/ecozones/borealshield/borealshield.htm (accessed July 20, 2006).

Belanger, Claude. 2006. Newfoundland Geography. http://www2.marianopolis.edu/nfldhistory/Newfoundland%geography.html (accessed July 28, 2006).

Colman-Sadd, S. and Scott, S.A. 1994. Newfoundland and Labrador Traveller’s Guide to the Geology. http://www.wordplay.com/geology/ (accessed July 28, 2006).

Cornish, Jim. 2003 [website] Gander, Newfoundland (accessed July 28, 2006)

Damman, A.W.H. 1983. An Ecological Subdivision of the Island of Newfoundland, pp. 163-206. South, G.R. (ed.), Biogeography and Ecology of the Island of Newfoundland. Dr.W. Junk Publ., The Hague.

Fuller, George D. 1919. Vegetation of Newfoundland. Botanical Gazette 67(1): 101.

Photography of Wildlife & Natural Areas of Newfoundland, Eco-regions (undated). http://wildnewfoundland.com/ecoregions.htm (accesssed on July 28, 2006).

Roberts, D. C. 1996. A Field Guide to Geology—Eastern North America. The Peterson Field Guide Series, Houghton Mifflin Company, New York.

Rogerson, R. J. 1983. Chapter 2. Geological Evolution. Pp5-35. South, G.R., ed. Biogeography and Ecology of the Island of Newfoundland, Dr W. Junk Publishers, The Hague.

Scott, Peter. 2005. The Origin of Newfoundland’s Flora. http://mun.ca/botgarden/plant_bio/ (accessed on July 28, 2006).

Wilson, J. T. 1966. Did the Atlantic Close and then Re-Open? Nature 211: 676-681.

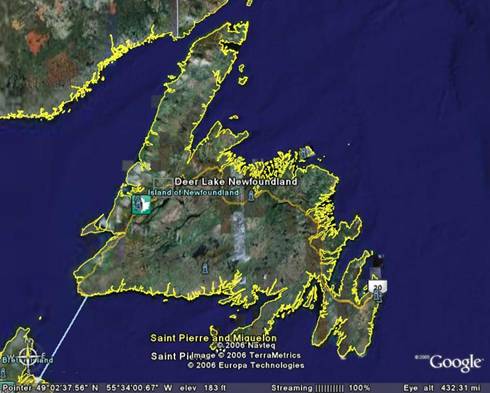

The large island of

Newfoundland lies off the east coast of North America, centered on

55º W longitude, and “between latitudes

46.5º N and 52º N.” The capital

(of Newfoundland and Laborador), St. John’s, is at the same

latitude as Sakhalin Island, Quebec, Duluth, Seattle and

Paris. “Newfoundland is triangular in shape, about

320 miles across and occupies an area of 43,000 square miles (the size

of Pennsylvania).” It lies on the continental

shelf, only 11 miles from Labrador on the mainland, and 70 from Cape

Breton, Nova Scotia. “The island is plateau-like,

with steep shores on all sides except the

northeast.” The plateau, which averages 1200 ft

above sea level (asl), sinks gradually to the east and

northeast. Scattered over the plateau surfaces are many

striking knobs or peaks rising several hundred feet above the general

level. An elongated block of the earth’s crust,

known as the Long Range, rises to nearly 2000 ft above sea level, along

the west coast. The highest point on the Long Range plateau

is in the Lewis Hills, and is 2673 ft asl; Gros Morne, 100 miles to the

northeast, is almost the same height. Deer Lake, where we

began our expedition, sits in a 20 mile wide depression to the east of

the Long Range (Belanger, 2006).

The large island of

Newfoundland lies off the east coast of North America, centered on

55º W longitude, and “between latitudes

46.5º N and 52º N.” The capital

(of Newfoundland and Laborador), St. John’s, is at the same

latitude as Sakhalin Island, Quebec, Duluth, Seattle and

Paris. “Newfoundland is triangular in shape, about

320 miles across and occupies an area of 43,000 square miles (the size

of Pennsylvania).” It lies on the continental

shelf, only 11 miles from Labrador on the mainland, and 70 from Cape

Breton, Nova Scotia. “The island is plateau-like,

with steep shores on all sides except the

northeast.” The plateau, which averages 1200 ft

above sea level (asl), sinks gradually to the east and

northeast. Scattered over the plateau surfaces are many

striking knobs or peaks rising several hundred feet above the general

level. An elongated block of the earth’s crust,

known as the Long Range, rises to nearly 2000 ft above sea level, along

the west coast. The highest point on the Long Range plateau

is in the Lewis Hills, and is 2673 ft asl; Gros Morne, 100 miles to the

northeast, is almost the same height. Deer Lake, where we

began our expedition, sits in a 20 mile wide depression to the east of

the Long Range (Belanger, 2006).